There’s one true measure of marketing effectiveness: Marketing(t)

Time is the variable that most defines marketing success, because consistent growth is the truest test of a brand and its team.

I have a friend called Mike. A Minnesotan. We weren’t super tight. But he was good company when I lived in the Twin Cities. Every now and again he’d call me up and, in that brief, affable midwestern way, ask if I “wanted to see a ballgame”.

Mike was a baseball tragic and took great pleasure in taking his one and only British friend to an occasional game. We’d sit in the cheap seats. Drink very weak beer. Eat peanuts. Watch the Twins lose. And glory in the magical pointlessness of baseball.

So, when my phone rang one Sunday night early in the 1998 season, I knew who it was. “Wanna see a ballgame tomorrow night?” Mike asked. From my hesitation, he must have guessed (correctly) that I was not keen. The Twins were a very mediocre side that year and the visiting Baltimore Orioles were not much better. Both would finish down the bottom rungs of their respective divisions come September. This was already apparent to even a baseball ignoramus like me. I was winding up to say no.

“Ripken is playing,” Mike said. “OK,” I replied, “Meet you at 6.”

The next evening, we walked the 10 blocks from my apartment to the already ancient Hubert H Humphrey Metrodome and paid $10 each to sit in the nosebleed seats. The stadium was 80% empty, which made its trademark vacant atmosphere feel all the more barren.

Down below, the players went through the motions and, if my memories from a quarter-century ago are correct, nothing particularly happened for the first few innings. We drank some bad beer. Talked about nothing. And watched batter after batter fail to have any impact.

Eventually Ripken appeared. And we both shut up. I remember him limbering up. Then sauntering up to the plate, much taller than I had expected. He swung and missed and before you knew it, he was back in the dugout. But both Mike and I had sat spellbound through the whole two minutes. As we would for each of his other three or four fruitless trips to the plate.

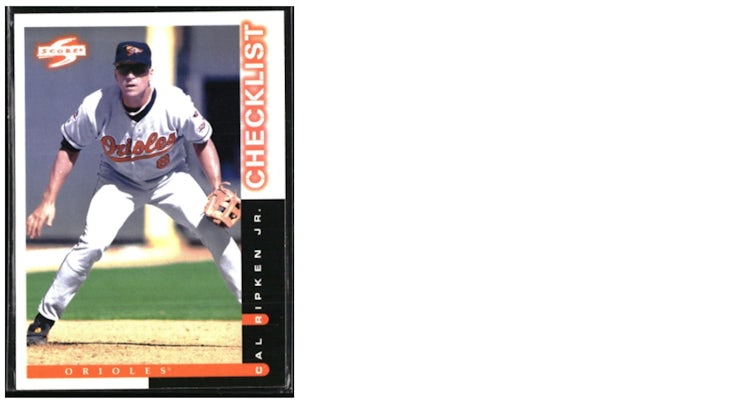

We weren’t there to watch the Twins or the Orioles that night. Like half the crowd, we had come to see Cal ‘Iron Man’ Ripken play ball. Specifically, we had come to see one of the 2,632 consecutive games of baseball that Ripken would play in what became a very famous baseball record. The streak started in May 1982 when Ripken was 22. He would play every single game for the Orioles over the next 16 years, deciding to eventually sit out a game at the back end of the 1998 season, six months after Mike and I watched the Iron Man in action.

It was and still is a peculiar record. Baseball at the time was all about the fastest pitch, the biggest home run, the most homers hit in a single season. In the middle of all this immediacy was this grey-haired, low-key player who was famous not for any one thing but for doing it for longer than anyone else. Ripken was a wonderful player, but there were others who grabbed more of the spotlight each season. What made him great – the source of his ‘Iron’ nickname – was his longevity. Time, the ‘t variable’, was his crowning achievement.

We talk too much about moments in marketing and not enough about marketing(t).

I say the t variable because that’s the best way to think about it. If you learned algebra, you will know that when you take any variable and then show its measurement across a regular integer value of time, it is shown as a t within parentheses. And the presence of that (t) changes how you look at the variable. It wasn’t Cal Ripken that got us to that game all those years ago. It was Cal Ripken(t).

And we can apply the same calculation to marketing. We focus on a lot of stuff like product launches, ads and revenue growth that are of the moment. And we look at these things in almost total isolation from what happened before. In doing so we miss the implication of time and the bigger picture that it paints. We talk too much about moments in marketing and not enough about marketing(t).

I’ll give you an example. Exactly two years ago everyone lost their collective marketing shit over that Prime energy drink. Do you remember? Influencers Logan Paul and Olajide Olatunji launched their energy drink globally and retailers sold out, the grey market was pricing a bottle at 10 times its RRP, and long lines of kids were photographed waiting patiently for a single bottle.

And then it all went flat. The lines disappeared. The product became overstocked. And you can now buy it for a fraction of its RRP. I’m sure its two founders made a fair profit over the last 12 months. Their marketing approach was genuinely successful. But if they understood marketing(t) they could have engineered a slower, more sustainable and ultimately more profitable approach.

Interbrand gets the t variable. The most famous brand valuation firm employs three distinct calculations to produce its annual league table of global brands. First there is a financial analysis to reveal how much money a brand is generating for its owners in the current period. Next comes an assessment of how much of that financial sum is driven by brand as opposed to other factors like price or availability. Finally, that now-revised amount is assessed against the t variable. Interbrand estimates brand strength and calculates how sustainable a brand’s strength will prove to be over the long term. The whole thing is essentially a net present value. And without the final crucial multiplier of time, any estimate of brand value would be meaningless.

Longevity

Bernard Arnault, the chairman and CEO of LVMH, gets it too. Boy, does he get it! I once watched an interview with him on French TV. Apple had just become the world’s most valuable brand and, just as his interview was about to close, the reporter asked for his thoughts on Apple given its newly won status. The French magnate was effusive in his praise for Steve Jobs and Apple but then paused. The faintest of smiles flickered across his face and Arnault hunched his shoulders and offered up one final observation. He was sure that clients in the far distant future would be drinking Dom Perignon and travelling with Louis Vuitton luggage. But he was less certain that would be the case for the iPhone.

The t variable. Arnault was politely but forcefully making his point that LVMH was not just currently one of the biggest companies in the world with one of the best portfolios of brands. LVMH(t) was in an infinitely better place than almost any other organisation, because of the slow-moving nature of the categories it exists in and the almost eternal attraction of the brands it operates within those categories. Apple, for all its current glory, was less attractive if you looked at Apple(t).

Occasionally, I am asked which brands impress me at the moment (it’s always at the moment). At the top of my list is Louis Vuitton. Not because it’s owned by Arnault. Not because I used to work for the brand. Not because it’s to my taste. And not because of a current campaign or successful show. I am impressed with Louis Vuitton(t). With the fact that every year for 20 years the brand has grown, and every year any subsequent growth gets harder. And yet every year Louis Vuitton grows again.

Adding the t variable adds not just data points but a valuable perspective, which is as sorely missed as it is incredibly important.

It’s not fair to say that anyone can build a brand for a year. Most people cannot even do that. But to build a brand and then maintain it – even grow it over many years – is a very different challenge. To create not just a successful brand but a successful brand(t) is a rarer achievement. One in which marketers not only create a strategy and calibrate their tactics for the year, but for the many years ahead. Truly that is where marketing awards should focus.

Too often, we are blinded by an immediate, ephemeral success and we miss the harder, more valuable consistency that the t variable points us towards. Indeed, marketing recognition seems biased towards those who can turn around a brand or fix one that is broken, rather than those who simply maintain one’s success. We stare in awe at the guy who will hit 50 home runs this season (and then retire) and ignore Cal Ripken quietly warming up for his 2,000th consecutive game in his 17th uninterrupted season.

The same logic applies to marketing management. You can take a snapshot of the people running a brand at any one time and look at their skills, intelligence and approach. But this is just the current marketing capability. The missing perspective of marketing(t) is how long the team has been in place at that brand. How long will they stay there? It’s true that the teams at Diageo, Cadbury, Tesco and Unilever consist of insanely talented marketing people. But they have mostly been in place for a decade or more. And the t makes the ultimate difference.

Not because old people are better than young people. I see that discussion a lot now, especially when people point to the ridiculous lack of people aged 40-plus within advertising agencies. That’s a problem. Not because Gen X is better than Gen Y. That argument makes no sense from either end. The issue with too many young people is that it is statistically less likely that any will have spent enough time on the job and in their role to be really good at it yet. I’m not going to take a 50-year-old over a 25-year-old, I’m going to find out which one has been doing the job longest because all other things being equal, the t variable will be the difference.

Marketing is an ephemeral endeavour. Brands are only as good as their last campaign or latest sales results. Perhaps that is an unavoidable aspect of capitalism in the early 21st century. But adding the t variable adds not just data points but a valuable perspective, which is as sorely missed as it is incredibly important.